Articles Menu

July 14, 2025

On a cloudy February morning in 2019, the owners of a century-old pulp mill in Port Alice, on northern Vancouver Island, told their workers to leave, shut off the power and “lock the gate.”

Inside, a sprawling waste site containing oil, asbestos, mercury, chlorine and carcinogenic chemicals stood at “imminent risk of failure.”

Six years and one landfill landslide later, the province has spent over $150 million to address the site’s immediate risks — but dangers remain, including unstable toxic waste landfills perched on cliffs overlooking Neroutsos Inlet, once a spawning site for Pacific salmon and in the traditional territory of the Quatsino First Nation.

Court documents and other information reviewed by The Tyee reveal a slow-brewing catastrophe at the mill in Port Alice, last known as Neucel and owned by a Chinese company called Fulida Group Holdings before it went bankrupt.

That includes a malfunctioning water treatment system that had been sending toxins directly into the inlet for up to four years.

According to the most recent court filing in May by PricewaterhouseCoopers Canada, the accounting firm appointed by the provincial government to co-ordinate the mill’s cleanup, the province spent $22 million on the cleanup last year alone. With at least another year of work ahead to close the landfill, the receiver is authorized to spend $170 million by next spring, and more public money will be required to finish the job.

Many of the mill’s seven historical owners opted for profits in place of maintenance and upgrades over its long history; by the late 1980s, Port Alice had earned the dubious distinction of being the province’s most polluting pulp mill. One long-term owner, Western Forest Products, emerged from bankruptcy proceedings by selling off the deteriorating mill and its toxins. The province, wanting to preserve jobs in the region, agreed to sweeten the deal for a future buyer by shouldering the cost of its historic contamination.

Three more bankruptcies later, Port Alice’s environmental debts are finally coming due. And they’re a harbinger of what’s to come across the province. Twelve pulp mill closures from Powell River to Mackenzie mean vast stores of toxic chemicals, some in tanks and some in the ground, will require closure and, for some, ongoing treatment.

That prompts two key questions, says Caitlin Pierzchalski, a restoration ecologist and executive director of the North Island advocacy organization Project Watershed. What will happen to these facilities? And, just as importantly, who is responsible for them?

When it comes to cleanup, B.C. is on the back foot. It has no usable laws allowing it to compel companies to shut down and restore their industrial sites. This regulatory void allows pulp mills and other sites to sit dormant for decades, even when their owners risk bankruptcy.

In other words: Port Alice isn’t the first time the province has paid industry’s cleanup bill. And it won’t be the last.

In an internal briefing note released via freedom of information request, B.C. acknowledged that Port Alice’s mill “is a symptom of a wider problem that faces the people of B.C., where taxpayers are ultimately bearing the cost for abandoned industrial sites that have no financial assurance.”

Galvanized by Port Alice’s example, the government in 2020 launched a new process to hold companies accountable for the messes they create.

But, long delayed, it now appears to be taking a back seat to the government’s goal to see shovels in the ground at new mining and LNG projects.

Port Alice’s chief administrative officer, Bonnie Danyk, hopes Port Alice’s story will be a cautionary one for the provincial government.

From boom to bust

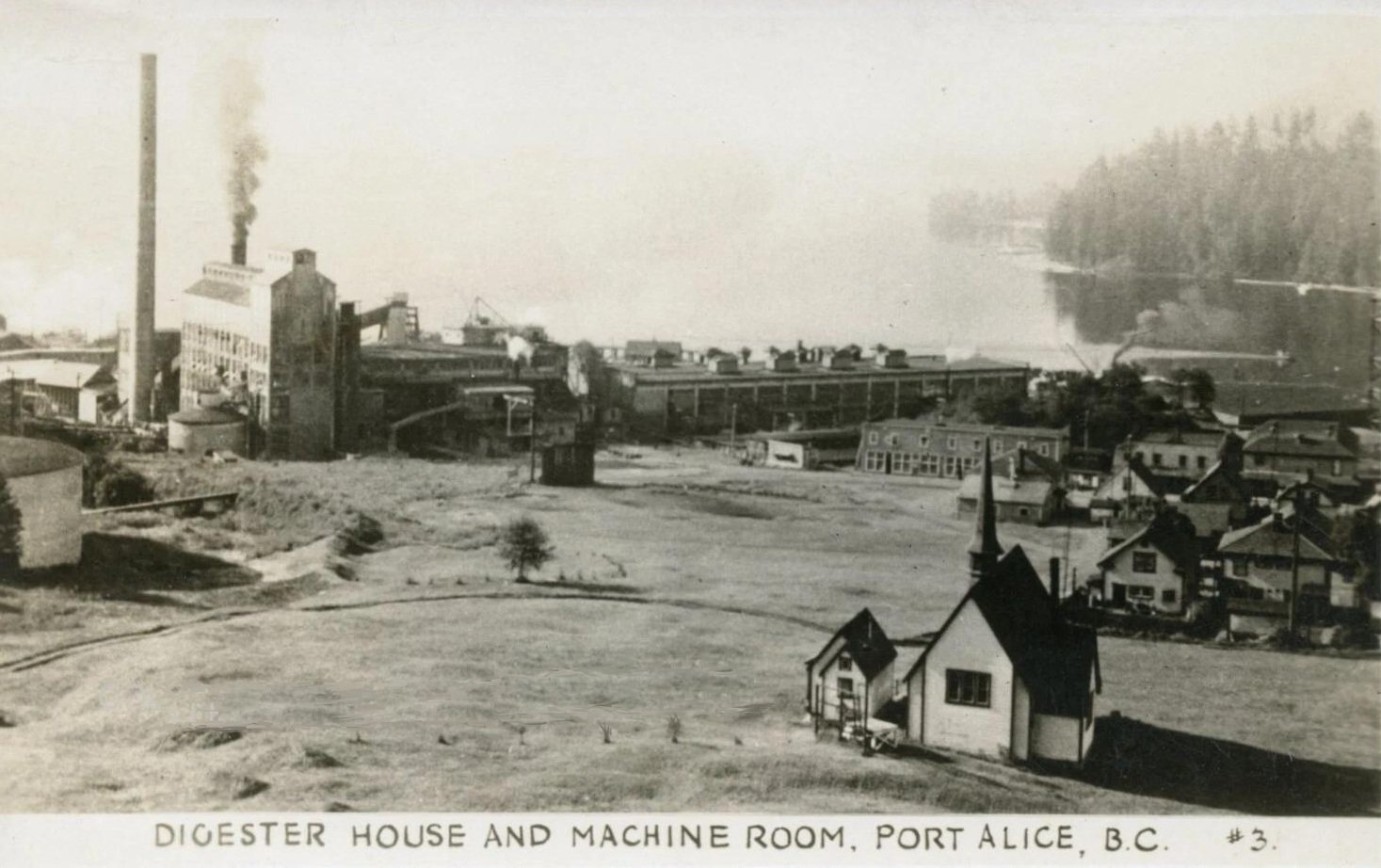

When it began operating in 1918, Port Alice’s mill was one of the province’s first, built to capitalize on the gold rush for wood pulp. Sulphite pulp, Port Alice’s particular variant, was useful for everything from viscose clothing and cigarette filters to the explosives used in the First and Second World Wars.

Tucked away in the long, sheltered Neroutsos Inlet, the mill was safe from open ocean weather while still offering seaside access to global markets. For decades, business was good: ships arrived with loads of chemicals and departed with mountains of pulp.

“Back then, everybody figured that the pulp and paper industry was a licence to print money,” said Don Vye, the mill’s former Unifor Local 514 president and longtime employee.

The town sprang up in the mill’s shadow, building houses beside its tanks and boilers. By the 1960s, a slew of sometimes lethal landslides had driven residents to relocate an eight-minute drive up the inlet. The pollution from the mill factored in too, Danyk told The Tyee.

Sulphite pulp making involves cooking wood chips in hot, pressurized vats of acid and then bathing and rinsing them in successive tanks of chemicals, including bleach. It’s a water-intensive affair: according to a 1956 report sourced by The Tyee, running the mill required 110,000 litres of water per minute from Victoria Lake, east of town.

For every tonne of pulp Port Alice produced, almost three tonnes of wastewater laced with wood fibre and chemicals were pumped directly into the inlet. Every year, that amounted to 22,000 lethal doses of mercury and six million kilograms of bleach.

The water turned black, carpeted with jelly-like mats of decaying sludge and covered with thick brown foam. Everything died within a 14-kilometre radius.

“When children swam in the area, they often had burns on their skin afterwards,” former Quatsino Chief Tom Nelson and council members wrote in a 2024 op-ed. The nation learned to avoid a wide area surrounding the mill, in the heart of their territory.

Later, it was discovered that pulp mills’ chemical soup included dioxin, a key ingredient in Agent Orange, and one of the most toxic compounds on earth. Dioxins can accumulate in humans, animals and environments, and contamination can lead to DNA disruption for generations. A wave of federal and provincial regulations eventually curbed dioxins in most B.C. pulp mills, but Port Alice, with its sulphite pulp and its shallow waterfront, would be an outlier, producing twice as much dioxin as any other mill in the province.

By the late 1970s, momentum was building to crack down on pulp effluent. At first, Port Alice’s then-owner, Rayonier, attempted to comply by dumping the waste into the open ocean. Even then, the pollution in the inlet remained too high for the new standards.

So they built a system to collect effluent, evaporate some of it, burn what they could, and throw the remaining sludge and ash products into a series of tanks and landfills. In theory, this would keep the contaminants isolated and safely stowed away.

But things wouldn’t turn out that way.

In the 1980s, the mill was taken over by Western Forest Products Ltd., a conglomerate of three B.C. forest companies: Doman Industries Ltd., Whonnock Industries Ltd. and British Columbia Forest Products Ltd. Its bankers decided to invest hundreds of millions to rebuild the company’s other mill, Woodfibre, and leave Port Alice with smaller upgrades and “custodial” upkeep, beginning its downhill trajectory.

Twenty years later, Doman had taken over the partnership and was bankrupt. A newly named company, Western Forest Products Inc., would emerge from the restructuring, except for one thing: it would cut Port Alice and its “unknown degree of environmental contamination” loose.

“There has to be a sacrifice of a part to save the whole,” said Vye, remembering conversations with lawyers and financiers at the time.

The Tyee requested comment from Western Forest Products but did not hear back by press time.

Western Forest Products would go on to be one of the province’s biggest forest companies, and Port Alice became its severed limb, selling for $1 to LaPointe Partners, a U.S. company whose chair, William New, had a reputation for buying and bankrupting pulp mills in the United States. Unsurprisingly, Port Alice followed suit, going bankrupt six months after its acquisition.

Employees alleged the company stole their pension contributions and benefits, prompting the RCMP to recommend charges. But the company’s owners, based in the United States, were never arrested.

Concerned about layoffs and job losses, the provincial government tried to find a new buyer, but its contaminants were an inhibitor. Claire Trevena, NDP MLA for the North Island at the time, was a staunch advocate for its revival. The mill was waiting, she said, “for some intervention by the government, not a subsidy but an intervention, to help facilitate this deal.”

That intervention came in the form of an agreement that B.C. would clean up the historic contaminants on the mill site.

But it only prolonged the inevitable. The mill would be abandoned by two more owners, and its contamination would only grow worse.

‘Every part of the site poses a significant environmental issue’

Three days after Port Alice mill workers were told to leave the premises in 2019, the province sent an environmental consulting firm, Nucor Environmental Solutions Ltd., to survey the damage.

“Without staff on site to actively maintain the mill at least to its current state, it is our opinion that within a very short time (possibly the first heavy rain event) the mill could suffer a catastrophic breech of one of more systems,” wrote its director, Andy Jeves in a letter to the province.

“All breeches will flow to the inlet.”

Containers of oil, some of them leaking, were scattered throughout the site. Pieces of the factory walls, likely containing asbestos, were falling multiple storeys to the ground.

“Every part of the site poses a significant environmental issue,” wrote Jeves. “By no means do we believe we have found all the dangerous goods located on the site.”

When they arrived on site, cleanup crews discovered that a metal-walled storage tank filled with eight million litres of liquid waste of “unknown human toxicity” had crumpled like folded paper, sending black sludge onto the ground.

They also found a damaged storage lagoon filled with toxic sludge that had been built atop an underground aquifer. Its lining had ripped, and it was now leaching its toxins into the water table.

Eventually, the province learned that the mill’s water treatment system wasn’t functional and that its toxic waste was “naturally discharging into Neroutsos Inlet.”

The mill had been non-operational for four years before it had been abandoned by Fulida Group Holdings in 2019, but had retained a skeleton staff to keep its systems running.

Once the province took control of the site that year, the company instructed the remaining manager to begin to “return the inventories” to “offset” the company’s debts. A sea can of materials worth $30,000 disappeared, as did a company boat worth up to $80,000. The company was forced into bankruptcy a year later. Its debts to the Bank of China, one of the company’s biggest lenders, have been repaid.

But the company’s debts in B.C. remain, including a BC Hydro bill of almost $400,000, at least $1.8 million in unpaid taxes to the town of Port Alice and around $4 million in unpaid severance pay to its workers.

While those debts are staggering, by far the highest price tag emerges from the mill site’s cleanup costs of $170 million and counting, which will be paid by the province’s citizens.

Unfinished business

Since the 1960s, Port Alice’s mill had deposited its wastes in various landfills, including a large one atop a cliff above Neroutsos Inlet where it placed things like asbestos and incinerator ash from burning effluent. A layer of sludge developed; it smelled like rot and hydrocarbons, according to an investigator.

Port Alice’s unlined, uncovered main landfill produces 88,000 litres of leachate — a mixture of water and chemicals that must be captured and processed to avoid further contamination — every day. Since at least 2005, the company and the province have known that leachate was leaking into groundwater and into the nearby North Creek, which flows into the inlet, though later reports found that leachate was diluted enough to meet provincial water guidelines.

The company and province also learned in 2005 that “tension cracks” had appeared upslope of the main landfill — a sign its contents were on the move. Inspectors warned that the landfill’s steep slope and the heavy local rains posed stability risks.

But recommended reinforcements, it was determined, were “cost prohibitive.”

In December 2023, a landfill south of the mill gave way, sending the equivalent of 3,000 large moving boxes of materials, including heavy oil, onto the road below. Two smaller slides occurred the following year. The province has since done upgrades to “reduce the likelihood of future slide events caused by rainfall.”

Meanwhile, efforts to reinforce the main landfill have pushed the project back, and it will be at least next summer before the problems at the landfill are addressed. It is unclear who will pay for the landfill’s permanent monitoring and maintenance that investigators say is required.

B.C.’s Ministry of Environment and Parks did not answer many of The Tyee’s questions about its responsibility for Port Alice’s ongoing environmental issues, given its 2005 agreement to address historic contaminants.

“The Province had fulfilled any obligations it had under that agreement prior to Neucel’s bankruptcy,” it said, in part, instead.

The ministry did not disclose those obligations, noting that “the agreement contains a confidentiality clause.” But the ministry did clarify that the main landfill “was the responsibility of Neucel,” and described various warnings and infractions it issued the company over its landfill management, including a $6,000 fine in 2019, two weeks before the company disappeared.

In an emailed statement to The Tyee, the Quatsino First Nation said it has ongoing concerns about the province’s cleanup approach and the failures of oversight that created the mill’s contamination in the first place.

“For decades, workers operated under unsafe conditions, and both corporate owners and public authorities failed to invest in the monitoring, protection, or rehabilitation of the site and surrounding areas,” it said.

The nation added that the province did not meaningfully engage them during the demolition process, nor consult on the future use and monitoring of the site, contravening its commitments to the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.

“The work completed to date has focused primarily on structural and storage risks — while overlooking or deferring the long-term environmental health and safety of the surrounding ecosystem and community,” it said.

“We believe the public deserves transparency and accuracy regarding the environmental risks that persist at the site.”

B.C. has still not conducted a detailed site investigation of the mill site to determine the extent of its contamination, despite calls from the Quatsino First Nation to do so.

“At this time, the Ministry of Environment and Parks does not intend to carry out a site investigation on the Port Alice Mill site to determine contaminants,” the ministry wrote in an email.

Is the fix in?

While the province says companies’ heyday of shirking their environmental debts is coming to a close, little has changed so far. The province still can’t compel companies to clean up their industrial sites — even if it’s clear they’re careening towards bankruptcy.

So companies often let their industrial sites deteriorate, sometimes letting them sit dormant for years, Sabrina Spencer, a partner focusing on Aboriginal and environmental law at Aird & Berlis LLP, told The Tyee.

Meanwhile, monitoring falls by the wayside. Here, Port Alice offers another example of what can go wrong: it stopped tracking its effluent when it ceased production in 2015, and the province didn’t check either. That means the province doesn’t know when its treatment system broke.

B.C. has no clear standards of what a fully remediated pulp mill or other industrial site requires, said Spencer. For example, Western Forest Products received a certificate for remediation for its closed Woodfibre pulp mill before selling the site to Woodfibre LNG in 2015. But it wasn’t required to close and cap the landfill, which spilled 3,000 litres of wastewater and leachate into the environment a year later.

Jeremy Valeriote, the MLA for the West Vancouver-Sea to Sky riding, where Woodfibre is located, told The Tyee he was “surprised” it had taken the government this long to put a public interest bonding strategy in place.

“This should have been taken care of decades ago,” Valeriote said.

“We’ve seen companies walk away from sites and leave taxpayers and the government holding the bag.”

Determined to mend its risky legal holes, B.C. launched a two-stage process in 2020.

The first part aimed to bring its laws for industrial sites, like pulp mills, gas stations and smelters, up to par with its rules for mines and oil and gas.

Those laws arrived in 2023. Like the rules already in place for oil, gas and mining, they theoretically give B.C. the power to assess companies’ likelihood of going bankrupt and, if concern is warranted, allow it to demand that companies clean up. The laws also allow the province to collect money from industry as bonding insurance should they fail to do so.

But these new laws remain toothless: they require still-nascent regulations to be enforced.

Now, two years behind their original timeline, the Ministry of Environment and Parks told The Tyee it anticipates those regulations “in the coming years.”

If it ever happens, the process’s second phase promises to bring a more fundamental overhaul. It would allow B.C. to collect money to deal with unforeseen disasters, such as the Mount Polley tailings dam breach. It could also extend remediation requirements to other sectors, like logging operations.

The process has received pushback, including from the Business Council of British Columbia, which warned of the dangers of retroactive rules that could change “the rules of development for companies already operating in B.C.”

Spencer told The Tyee some caution will be needed to ensure the process doesn’t send a swath of companies into bankruptcy, ultimately losing the chance to get them to clean up their messes in the first place.

But B.C.’s current approach of slow-walking the process could also prove costly, and for many of its pulp mills, it might already be too late.

Over half of B.C.’s 24 pulp mills have already closed. Taxpayers have already paid for cleanup at some of them, like the Ocean Falls pulp mill west of Bella Coola and the Watson Island pulp mill near Prince Rupert. Other mills have been sold for bargain prices to private equity firms and other companies intent on transforming them into holding sites for fracking sand or bitcoin mining centres. The province might face an uphill battle getting companies like those to pay to clean up the the pulp mills they bought, Spencer told The Tyee.

As Trump’s tariffs and global tensions roil, Canadian governments appear to be in a building mood, launching expedited laws to fast-track projects. Calls to grapple with the final act of that development — closure — may seem a bit off-key.

But in the push-pull between starting new projects and cleaning up the old ones, Port Alice offers a worrisome example — both environmentally and economically — of what will happen if the province doesn’t batten down its regulatory hatches.

“If we have a couple more Neucels down the road, that’s a pretty big hit for taxpayers,” Spencer said.

Zoë Yunker is a Victoria-based journalist writing about environmental politics. Follow her on BlueSky @zoeyunker.bsky.social.

[Top photo: Toxins leak from a crumpled storage tank at the bankrupted Port Alice mill. Due to lax regulations, the BC public will pay for cleanup. Photo via PricewaterhouseCoopers.]